Over the years, video games have grown into a larger industry than movies, television, and music. Intellectual property has always been a key driver in the business of video games, with disputes between players big and small on patents, copyrights, and trademarks. As the industry has grown, the intellectual property issues have leveled up too.

Banner Witcoff attorneys Ross Dannenberg and Scott M. Kelly serve as editors at the Patent Arcade, a site Ross founded in April 2005, where they and other members of our team write on current and historical intellectual property issues in the video game industry. As we celebrate National Video Game Day, here’s some of the legal disputes that have helped define the industry.

Video Games & Patents

The first major video game case, Magnavox Co. v. Activision, Inc.[1] was a patent infringement lawsuit that hinged on purely functional aspects. Magnavox’s Odyssey game console, the inspiration for Pong and synonymous with early video games, allowed two players to bounce a white dot back-and-forth simulating digital ping-pong. Magnavox pursued broad patent protection over its gaming devices, claim 51 of its patent reciting:

51. Apparatus for generating symbols upon the screen of a television receiver to be manipulated by at least one participant, comprising:

means for generating a hitting symbol; and

means for generating a hit symbol including means for ascertaining coincidence between said hitting symbol and said hit symbol and means for imparting a distinct motion to said hit symbol upon coincidence.[2]

Several of Activision’s games throughout the 1980s had a “ball and paddle” format similar to that described by Magnavox’s patent. When Magnovox claimed infringement against Activision the litigation, it was highly technical. The litigation focused on technical aspects of the Magnavox Odyssey and Activision’s games, including a contention by Activision that the claim elements were recited in so-called means-plus-function format (which requires that a claim be interpreted based on the physical hardware (means) described in the patent to perform the claimed functions). Activision wanted to limit the interpretation of the patent claims to only the technology that was available at the time. If they prevailed in doing so, they could have potentially escaped infringement because the technology they used was physically different. The court, however, rejected this argument.

The court’s holding in favor of Magnavox foreshadowed the future of video game law, stating: “the use of currently available technology to implement television games does not alter the basic nature of those games or avoid [Magnavox’s] patent.”[3] The court took into account advances in technology and saw Magnavox’s patent as something beyond specific circuitry on a circuit board.[4] The court’s holding hinted that the court saw the ‘basic nature of those games’ as something more – that a video game patent is as much about protecting the resultant expression represented by the game as it is the cold, technical, functional aspects that make that expression a playable reality.

In the end, the court held Activision liable for patent

infringement and Magnavox went on to enforce its patents against virtually

every game publisher whose game used a ball and paddle format of any kind.

Video Games & Copyrights

Copyright protects creative works of original authorship that are fixed in a tangible form. In the business of video games, this may include artwork, new content, or any content likely to be copied by others.

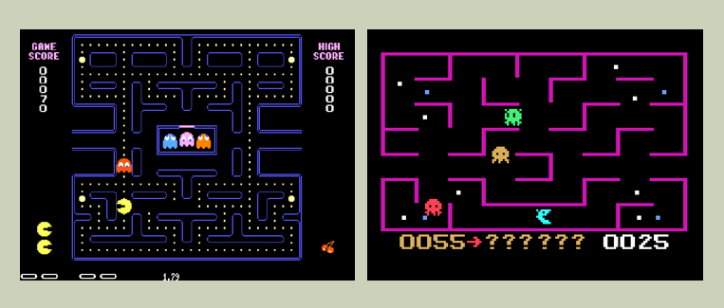

Atari v. North American Philips was an early case regarding copyright protection of video games, in which the court addressed the issue of determining the scope of copyright protection in an audiovisual work such as a video game. The question: Did North American Phillips’ game K.C.MUNCHKIN infringe Atari’s copyright in the game PAC-MAN? The court, noting that a game is not protectible by copyright “as such,” stated that video games are protectible “at least to a limited extent [insofar as] the particular form in which it is expressed provides something new or additional over the idea.” The court went on to conclude that Atari had a likelihood of success on the merits of the copyright infringement claim, and granted a preliminary injunction preventing North American Phillips from infringing Atari’s copyright by producing the K.C.MUNCHKIN game.

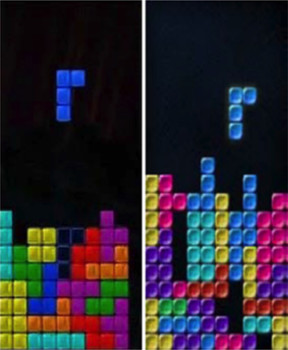

Another notable case for video game copyrights is Tetris Holding, LLC v. Xio Interactive, Inc. Since its launch in the 1980s, Tetris has expanded to a global scale and is now a cultural icon.[5] Xio was inspired by Tetris to create a multiplayer game for mobile called Mino. Mino was admittedly a clone of Tetris, but Xio argued it copied only unprotectable functional aspects of Tetris, because the game’s simplistic design necessitates certain choices.[6] Tetris argued that Mino infringed on its copyright by copying, virtually identically, most of Tetris.[7] The court held there were still many protectable aspects, stating “Tetris Holding is as entitled to copyright protection for the way in which it chooses to express game rules or game play as one would be to the way in which one chooses to express an idea.”[8]

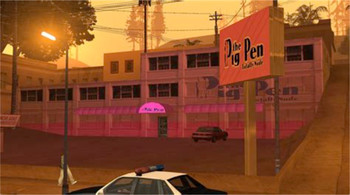

Video Games & Trademarks Rockstar Games is the developer of the wildly popular Grand Theft Auto video game series.[9] Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas featured the city of ‘Los Santos’ that was heavily based on real-life Los Angeles and its various neighborhoods.[10] E.S.S. Entertainment is a real-life company that operates a strip club in downtown Los Angeles called the Play Pen Gentleman’s Club, with the words ‘the Play Pen’ and ‘Totally Nude’ in a public-facing sign, and featuring a nude female dancer in the stem of the first ‘P’.[11] Rockstar, drawing inspiration from the club, included its own strip club in San Andreas called the ‘Pig Pen’ with a sign that was similar but without, for example, the ‘Totally Nude’ signage.[12] E.S.S. sued Rockstar for trademark infringement.

The Ninth Circuit was not persuaded by E.S.S.’s arguments. The court applied the Rogers v. Grimaldi test,[13] balancing “Rockstar’s artistic goal, which was to develop a cartoon-style parody of East Los Angeles” with “whether the game would confuse its players into thinking that the Play Pen is somehow behind the Pig Pen or that it sponsors Rockstar’s product.”[14] The Rogers test is a two-pronged test that holds that an artistic work’s use of a trademark is not an infringement “unless the [use of the mark] has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or, if it has some artistic relevance, unless [it] explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.”[15] Based on the Rogers test, the court found that no such confusion existed.

Banner Witcoff Patent Examples

Banner Witcoff has had its own part in shaping the history of video games, with extensive experience prosecuting patents in the video game space, with many of the patents we’ve prosecuted relating to some of the coolest aspects of modern video games. Below are just a few examples of the work we have done.

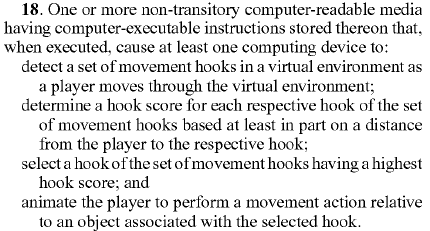

- Patent No.: US 8979652 B1, which relates to the video game “Dying Light” by Techland, and describes player movement control and animation in the popular zombie-apocalypse parkour game.

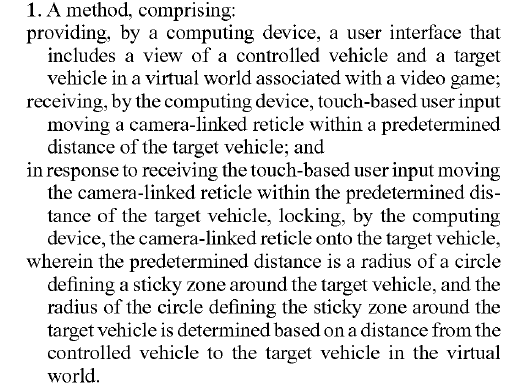

- Patent No.: US 9004997 B1, which relates to the video game “World of Tanks Blitz” by Wargaming, which describes a targeting reticle having features that could assist mobile users.

Conclusion

The cases outlined above make it clear that video game law has leveled up. Historic cases – which, in terms of video games, means only about 40 years ago – granted lesser protection to video games, resulting in more broadly permitted copying. That tide has now shifted. We have begun to see that US courts are willing to grant significant and increasingly broader intellectual property protections to games. Whereas video games were once in legal purgatory – being granted little meaningful protection by copyrights and patents alike– much like we have seen with books, plays and movies. As time goes on, the gaming industry will continue to grow, and the courts will naturally grow with it.

Attorneys at Banner Witcoff have developed the Patent Arcade, a blog to cover the intersection of IP law and video games. Click here to dive into the world of video game IP law at the Patent Arcade.

Some Recent Patent Arcade Posts:

- Animation Frames Patents Spotlight

- 28th Anniversary of Magic: The Gathering – A discussion of IP Considerations

- Hasbro’s Right of Ownership to the Game of Life’s IP Affirmed

[1] No. C-82-5270-CAL, 1985 WL 9496 (N.D. Cal. December 27, 1985), aff’d, 848 F.2d 1244 (Fed. Cir. 1988).

[2] U.S. Reissue Patent No. RE28, 507 col. 31, l. 57-65 (filed April 25, 1974) (available at https://patents.google.com/patent/USRE28507).

[3] Ibid at *16

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid at 397.

[7] Ibid at 397–98.

[8] Ibid at 405.

[9] Andrew Goldfarb, GTA 5 makes $800 Million in one day , IGN ( September 18 , 2013 , 12:02 PM PDT), http://www.ign.com/articles/2013/09/18/gta-5-makes-800-million-in-one-day .

[10] E.S.S. Entm’t 2000, Inc. v. Rock Star Videos, Inc., 547 F.3d 1095, 1097 (9th Cir. 2008).

[11] Ibid at 1097.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994, 999 (2nd Cir. 1989).

[14] E.S.S. Entm’t 2000, 547 F.3d 1095 at 1100.

[15] Rogers, 875 F.2d at 999.

Posted: September 12, 2021