By Brad Van Pelt, Alisa Abbott, Rob Katz

February 6, 2024 — Yesterday the entire U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“Federal Circuit”) sitting en banc for the first time in five years heard oral arguments in a closely watched case concerning design patent validity standards in a dispute between an automotive aftermarket parts provider, LKQ, and automaker, General Motors. The en banc panel consisted of Chief Judge Moore, Judges Lourie, Dyk, Prost, Reyna, Taranto, Chen, Hughes, Stoll, and Stark.

From the questioning and discussion, it appears that there is a possibility that the Federal Circuit’s decision could provide new standards and guidance when making the determination of design patent validity, but we will have to await the Federal Circuit’s decision, which should come out later this year.

Background

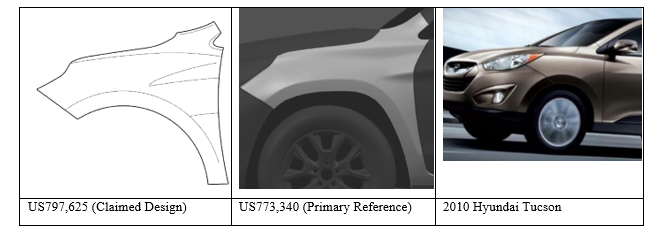

At issue in the appeal is the standard for obviousness in determining the validity of design patents. Previously, GM licensed LKQ as an approved repair part provider. But after negotiations fell through to renew LKQ’s license, GM informed LKQ that they were no longer authorized to sell GM replacement parts and asserted that LKQ infringed GM’s design patents. LKQ responded by attempting to invalidate a GM fender design patent, US797,625 (“the ‘625 patent”) at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) in an Inter Partes Review (“IPR”). In particular, LKQ argued that the ‘625 patent was obvious in view of US773,340 over the 2010 Hyundai Tucson, as illustrated below.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB” – the body within the USPTO that hears challenges to patents) held that LKQ did not show the ‘625 patent to be unpatentable because LKQ failed to identify a reference that was “basically the same” as the claimed design under the Rosen/Durling test. LKQ appealed this decision to the Federal Circuit arguing that the standard for reviewing design patents is inconsistent with Supreme Court and Federal Circuit precedent, and the standard must be adjusted to more closely follow utility patent standards for obviousness. The three-judge panel’s decision at the Federal Circuit authored by Judge Stoll disagreed and affirmed the PTAB’s decision that LKQ did not show the GM ‘625 patent to be unpatentable. The Federal Circuit granted LKQ’s petition for rehearing en banc.

Under the current obviousness standard for design patents, a patent challenger is first required to provide a single primary reference as a starting point to show that “the design characteristics … are basically the same as the claimed design in order to support a holding of obviousness.” Second, once a primary reference has been identified, the patent challenger may use other secondary references to modify the primary reference “to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.” But those secondary references must be “so related [to the primary reference] that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.”

The Oral Arguments

Mark Lemley began the oral arguments, speaking on behalf of LKQ, and argued that it’s much too difficult to find design patents obvious and sought a less rigorous obviousness test. Lemley argued that Rosen and Durling are inconsistent with the holding in KSR. According to Lemley, the tests in Rosen and Durling preclude use of any outside reference that is not basically the same as the claimed design in the flexible way required by KSR. Also, he said KSR makes it clear that the sources to which the patent challenger can look to for obviousness are not limited to the prior art itself. The above, Lemley argued, makes KSR and Rosen/Durling inconsistent. However, Lemley did not provide any specific outline for an alternative test. The panel seemed concerned that KSR would not carry over well to designs (such as the various rationales that might support a finding of obviousness under KSR including a reasonable expectation of success in combining prior art, simple substitution of one component for another, and addressing technical problems associated with utility patents). Finally, during Lemley’s rebuttal time at least one judge indicated that they are not in favor of overruling Durling and Rosen.

USPTO Acting Solicitor Farheena Rasheed spoke on behalf of the USPTO, asking the Court to set forth a new test and remand the case to reevaluate it based on the new test. Solicitor Rasheed urged the court to resist LKQ’s reading of KSR, and to use the “basically the same” test that the USPTO has been using for several years. But Solicitor Rasheed suggested a “softening” of the current test, without articulating more specifics on how the USPTO’s proposal differs from the current test when pressed by the panel. There was discussion over what type of prior art Examiners would search for, and Solicitor Rasheed clarified that Examiners should look to the art provided by the applicant and with that information, are able to consider what one of ordinary skill in the art might look to for prior art (for example, a furniture designer might look to architecture for inspiration). Solicitor Rasheed also stated that in most circumstances, a single primary reference often resolves the case, and that secondary sources are not frequently used. She urged the Federal Circuit to not replace one rigid test with another.

Joe Herriges, representing GM, was questioned on how the anticipation “substantially the same” test and the obviousness “basically the same” test differ. Herriges argued for preserving the current test, and suggested that LKQ is overstating the rigidity of the requirements provided by Rosen and Durling. Herriges stated that analogous art for obviousness needs to be the same article of manufacture, or something sufficiently similar. Overall, as one would predict, Herriges is happy with the current conception of the standard and how its applied. Notably, during Herriges argument, the judges grappled with the fact that obviousness is viewed by an ordinary designer (with a more discerning perspective) whereas infringement is determined by an ordinary observer (with a less discerning perspective) meaning that the standards could be different for patentability and infringement and one could easily obtain a design patent and successfully assert it.

The oral arguments did not seem to articulate a test that would replace Rosen and Durling. And there were no firm takeaways from the decision. The Federal Circuit now has the opportunity to affirm or otherwise articulate some additional legal guidance in evaluating the question of obviousness in design patents and/or overrule Rosen and Durling altogether. But we will have to wait and see whether and how the standard for obviousness changes for design patents until the Federal Circuit issues its en banc decision.

Posted: February 6, 2024