Monkey See, Monkey Do: Ninth Circuit Declines to Go Bananas over “Monkey Selfie” Copyrights

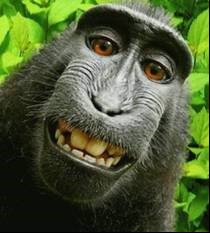

Ten years ago, a professional wildlife photographer’s camera captured some “selfies” of Naruto, a crested macaque living deep in the rain forests of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

Ten years ago, a professional wildlife photographer’s camera captured some “selfies” of Naruto, a crested macaque living deep in the rain forests of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

After the photographer published the photos, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) sued on the monkey’s behalf, claiming copyright infringement because the monkey authored the photos. The photographer acknowledged that Naruto clicked the shutter button, but claims that the selfies only happened because of his ingenuity, setup and perseverance. The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California dismissed the lawsuit on the ground that animals lack statutory standing to sue for copyright infringement.

On April 23, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed in a more forceful opinion against PETA. Among other things, the Ninth Circuit said that it “gravely doubt[ed]” whether PETA could sue on behalf of the monkey. The “next friend” doctrine typically governs when someone can sue on behalf of another, and it requires a mental incapacity or other disability. Moreover, the “next friend” doctrine also requires that the next friend “have some significant relationship with, and is truly dedicated to the best interests of” the disabled party. Here, the Ninth Circuit focused on the fact that PETA didn’t have any special relationship with the monkey that went beyond its relationships with other animals (the Ninth Circuit was less concerned with whether animals per se have a disability).

Next, and after acknowledging what seems to be relatively settled law that the U.S. Constitution does not automatically forbid lawsuits brought in the name of animals, the Ninth Circuit returned to affirming the district court’s ruling that next friend status to sue on behalf of an animal is controlled by the underlying, substantive statute—here the copyright statute. PETA tried to argue that since the copyright statute allows non-human entities like corporations to author copyrights (via the work made for hire doctrine), then animals can be authors and sue as well. But the Ninth Circuit followed its precedent in a case brought on behalf of cetaceans against the U.S. Navy using sonar, and said that permission for animals to sue must be “plainly stated” in the statute (and there is no such statement in the Copyright Act).

In a final blow to PETA, the Ninth Circuit said that the photographer and his company are entitled to legal fees from PETA, and remanded the case to the district court for further review. Even under copyright law, where a statute expressly states that attorney fees may be awarded to the “prevailing party,” such grants of legal fees are uncommon in the Ninth Circuit.

It is important to remember that the case is based largely on Ninth Circuit law, which is not binding on other circuits. But it is available as persuasive precedent, and it seems that the ability for animals to sue under various causes of action may largely depend on whether the underlying statutes expressly authorize animal lawsuits. Thus, copyright may be a challenge for animal selfies, but other intellectual property rights such as trademark, which is use-based not creator-based, may apply, as has been alleged with the dog “Lassie” and, more recently, the “Grumpy Cat” featured on the YouTube service. There even remain open questions as to whether animals may enjoy a right of publicity. Moreover, as artificial intelligence grows in popularity, it is possible that this ruling could be analogized to argue a lack of statutory standing to assert copyright infringement of AI-created works.

As for entities like PETA, the liability for the photographer’s attorney fees may have a chilling effect, and the next friend analysis in the Ninth Circuit’s ruling chips away at these entities’ ability to sue on behalf of animals merely because of their stated mission to support animal rights.

Click here to download the decision in Naruto v. Slater.

Posted: May 3, 2018