Supreme Court Oral Arguments in Samsung v. Apple

Oral arguments were held on Oct. 11, 2016, at the U.S. Supreme Court in the closely-watched and longstanding design patent suit between Apple and Samsung[1], and from the questioning and discussion, it appears that the Supreme Court’s decision will likely provide some new legal standards and points to consider when design patent damages are awarded.

Background

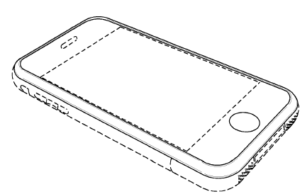

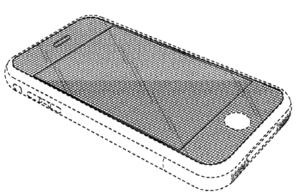

At issue in this appeal is the $399 million award that Samsung was ordered to pay Apple for infringement of several of Apple’s design patents. In particular, the jury found that several of Samsung’s smartphones infringed three of Apple’s design patents (D604,305, D593,087, and D618,677). The designs claimed in the Apple design patents are shown below:

D593,087

D604,305

The $399 million amounted to the entirety of Samsung’s profits from several of the infringing smartphones[2]. This award, affirmed on appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, stemmed from the application of 35 U.S.C. 289, which addresses design patent remedies with the following (emphasis added):

Whoever during the term of a patent for a design, without license of the owner, (1) applies the patented design, or any colorable imitation thereof, to any article of manufacture for the purpose of sale, or (2) sells or exposes for sale any article of manufacture to which such design or colorable imitation has been applied shall be liable to the owner to the extent of his total profit, but not less than $250, recoverable in any United States district court having jurisdiction of the parties.

Nothing in this section shall prevent, lessen, or impeach any other remedy which an owner of an infringed patent has under the provisions of this title, but he shall not twice recover the profit made from the infringement.

The award of the entirety of the profits was based on the “total profit” referenced in Section 289.

In its appeal brief, Samsung argued that the focus in Section 289 should be on the “article of manufacture to which” the design is applied, and that this “article of manufacture” could be a component of an item sold to the public. Samsung also argued that the legislative history behind the “total profit” concept was focused on articles whose value was driven by design (e.g., carpets, wallpapers), and that unfair and absurd results could come about from that rule if applied to more complicated items (e.g., a design patent on an automobile cupholder could warrant damages in the amount of the entire total profit of an automobile).

Apple responded in its brief by agreeing with Samsung that Section 289 does not create a per se rule that infringement of a design patent by a component of a device automatically, and always, entitles the plaintiff to an award of the total profit of the entire device. However, Apple argued that it was Samsung’s burden to offer proof of a smaller “article of manufacture” if it didn’t want damages based on the entire product, and that Samsung failed to do so (Apple noted that Samsung’s own damages expert based the damages calculations on the total profit of the entire phone). Apple also argued that the “total profit” rule had been properly applied by the courts in view of the legislative history, and that the hypothetical absurd results posited by Samsung would not actually occur since the “article of manufacture” could be properly established.

The Oral Arguments

The “article of manufacture” analysis took center stage at the oral arguments. Samsung argued that both parties agreed that the analysis should begin with a proper identification of the “article of manufacture.” Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kennedy both expressed concern about the form of the jury instructions, asking how a jury should be instructed on identifying an “article of manufacture.” Samsung replied that the jury, having the task of determining infringement anyway, could simply be asked to look at the patent figures and the accused product, and identify what they consider to be the “article of manufacture to which the design (from the design patent) applies.”

Justice Breyer noted that both parties, as well as the United States, essentially seemed to espouse a two-part test. The first part involved identifying what the “article of manufacture” was, and the second part involved determining the extent to which that “article of manufacture” was the reason for the infringer’s profits. Several Justices referred back to this two-part test throughout the discussion, often times using a hypothetical example of a Volkswagen Beetle automobile. Justice Kennedy pondered how the second part would be analyzed if, for example, the design for the Beetle occurred in a relatively short “flash of genius,” while developing the rest of the Beetle took a hundred thousand hours. Samsung responded by saying that in that situation, if the aesthetic design of the Beetle (as opposed to, for example, the car’s performance or internal details) were proven to be the sole reason people bought the car, then an award of 100 percent of the profits could still be justified.

Justice Sotomayor noted that the United States had offered a four-factor analysis in determining the relevant “article of manufacture,” and Apple conceded that those factors could indeed be part of the analysis. Those factors were as follows:

- The scope of the design claimed in the patent;

- The relative prominence of the design within the product as a whole;

- Whether the design is conceptually distinct from the product as a whole (they give the example of a book binding being conceptually distinct from the copyrighted contents of the book); and

- The physical relationship between the patented design and the rest of the product.

Justice Kennedy noted, with some bemusement, that this determination of the “article of manufacture” as a sub-component of an item sounded a lot like the “apportionment” of damages that, in the briefing and appeals below, was deemed improper in view of prior Section 289 jurisprudence. Apple noted that the key distinction here is that the “article of manufacture” analysis involves actually identifying a “thing,” whereas the prior jurisprudence “apportionment” focused on attempting to place a value on the design itself separate from the value of the actual item.Although the discussion focused on the “article of manufacture” analysis, there were a few instances addressing the record below. Apple’s core (sorry for the pun) argument was that even had the jury been given a different instruction on the “article of manufacture” analysis, Samsung’s own evidence focused on the entire value of the phones anyway, so there would have been no basis on the record for the jury to have concluded differently on the question of damages. Justice Sotomayor picked up on this, and wondered whether the current record would have supported a contrary finding by the jury. Justice Ginsburg also explored the topic, asking if Samsung had attempted to provide evidence of damages for less than the entire product. Samsung said it tried numerous times to do so, but that its efforts were thwarted by the lower court’s interpretation of the “total profit” rule. Apple argued that, to the contrary, Samsung actually had “every opportunity” to offer the necessary evidence to support an alternative damages finding.Justice Breyer seemed rather uninterested in discussing the details of the factual record below, and seemed inclined to articulate the legal standard for the “article of manufacture” analysis, and to remand the case for further proceedings accordingly.

Conclusion and Takeaways

No firm takeaways will be known until the decision, but based on the questions, it at least appears likely that the Supreme Court will be articulating some legal guidance in the interpretation and application of Section 289, and that this legal guidance will likely involve the two-step inquiry that was discussed at oral argument. The four factors identified in the United States’ brief may well also be included as examples in that analysis. As for whether the $399 million will stand, we will have to wait and see.

Please click here to download a printable version of this article.

[1] Samsung Electronics Co. et al. v. Apple Inc., No. 15-777 (U.S. December 16, 2015)

[2] The damages for infringement of one of the patents, the ‘087 patent, were not included in the $399 million, and were not at issue in this appeal.

Posted: October 12, 2016